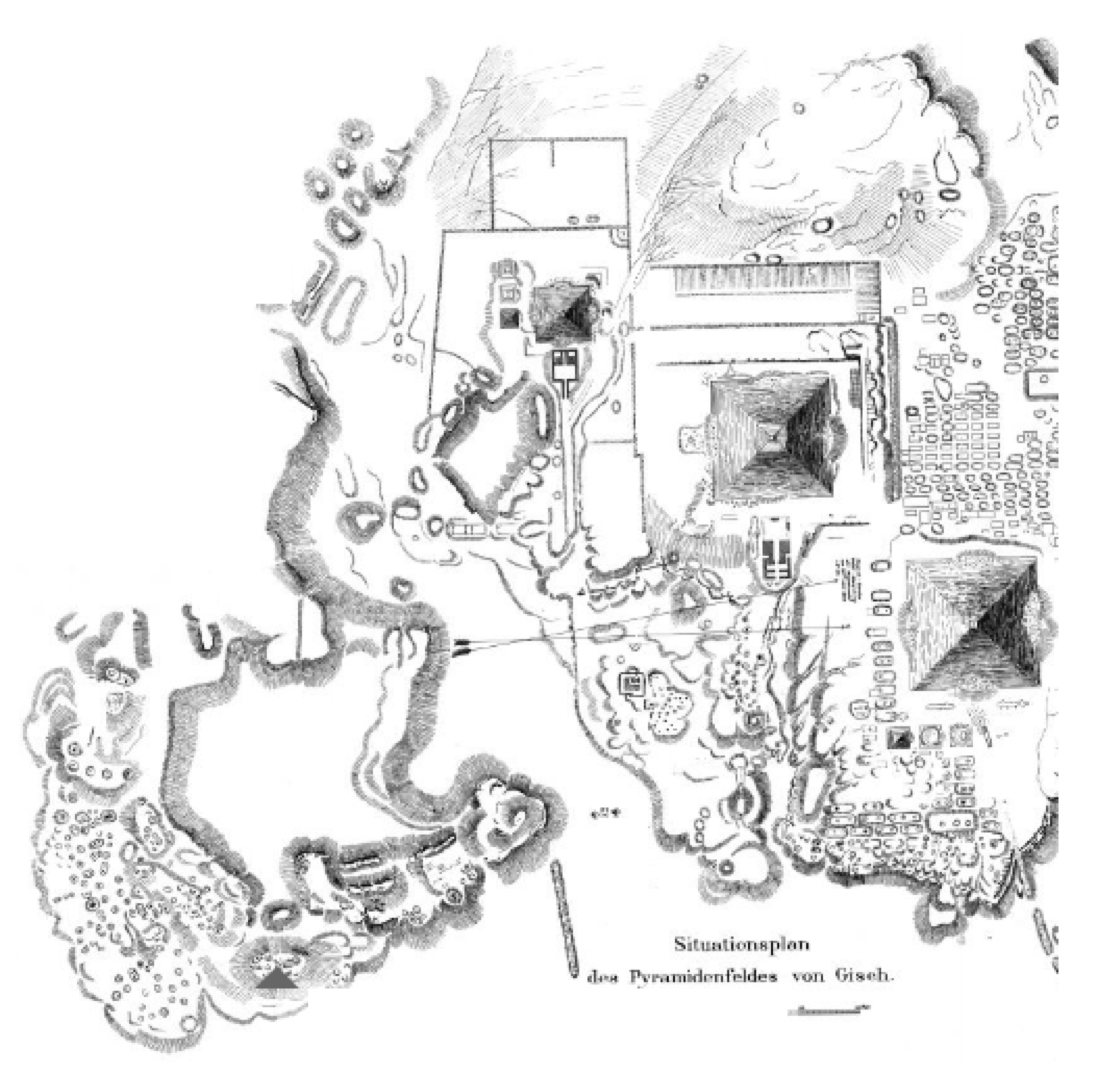

Maps and plans: General plan of Western Cemetery

-

- Tomb Owner

- Pepi (D 23)

-

- Attested

- Khenut (in D 23)

- Rashepses (in D 23)

- Rashepses (in D 23)

-

- Excavator

- Georg Steindorff, German, 1861–1951

-

- PorterMoss Date

- Dynasty 5

-

- Site Type

- Stone+Brick-built mastaba

-

- Shafts

- D 23,1; D 23,2; D 23,3; D 23,4; D 23,5; D 23,6; D 23,7; D 23,8; D 23,Serdab

-

- Remarks

- Mastaba is field south of D 100 and west of G 4000, just east of D 49, south of D 8, and wesd of D 13. Mastaba is drawn but not labeled on plan EG002029.

-

- Problems/Questions

- Grimm, Alfred [Hrsg.], Steindorff, Georg and Uvo Hölscher, Die Mastabas westlich der Cheopspyramide (...), S. 33f., Taf. 3.

-

- RPM_17

-

Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. "Pseudo-Groups." In Rainer Stadelmann and Hourig Sourouzian, eds. Kunst des Alten Reiches: Symposium im Deutschen Archäologischen Institut Kairo am 29. und 30. Oktober 1991. Sonderschrift des Deutschen Archäologischen Institut Abteilung Kairo 28, Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1995, pp. 58-59, n. 18.

Jánosi, Peter. "Review of Georg Steindorff and Uvo Holscher, Die Mastabas westlich der Cheopspyramide, Munchner Agyptologische Untersuchungen 21 (Frankfort am Mainz, 1991)." Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes 83 (1993), p. 257.

Kayser, Das Pelizaeus-Museum in Hildesheim (1966), Abb. 12

Lehmann, Katja. Der Serdab in den Privatgräbern des Alten Reiches 1-3. Ph.D. Dissertation, Universität Heidelberg, 2000, Kat. G10-G11.

Porter, Bertha, and Rosalind L.B. Moss. Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings 3: Memphis (Abû Rawâsh to Dahshûr). Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1931. 2nd edition. 3: Memphis, Part 1 (Abû Rawâsh to Abûsîr), revised and augmented by Jaromír Málek. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1974, p. 110, plan 14.

Steindorff, Georg, and Uvo Hölscher. Die Mastabas westlich der Cheopspyramide 1-2. Edited by Alfred Grimm. Münchner Ägyptologische Untersuchungen 2. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1991, pp. 33-34, pl. 3.

Ancient People

-

- Type Attested

- Remarks Alabaster offering basin (Leipzig 3125) inscribed for Khenut, identified as [rxt nswt] royal acquaintance; found at northeast corner of D 23.

-

- Type Tomb Owner

- Remarks Owner (?) of D 23. Limestone standing group statue (Hildesheim 17) of Pepi and two male figures (her sons ?), both named Rashepses; Pepi identified as [rxt nswt] royal acquaintance; found displaced in D 23, shaft 5. There are three possibilities as to who is actually represented in this statue: 1) Rashepses, his wife Pepi, and their son Rashepses. If this is true, then the craftsman who inscribed the piece switched the two Rashepses inscriptions, labeling the man as [sA=s raSpss] "her son Rashepses" and the boy as [wab nswt raSpss] "royal wab-priest Rashepses". This seems unlikely because the focal point of the group (the central, largest figure) is clearly Pepi, which would be quite unusual in a normal family statue. Also, the son is labeled "her son", not "his son" or "their son". 2) A so-called "pseudo-group", representing Pepi with her son Rashepses who appears twice at different ages. If this is the case, then the labels are more understandable; as a small boy, his size, nakedness and side lock all indicate that Rashepses must be the son of a nearby adult (i.e. Pepi) without it needing to be spelled out. However, the larger figure of Rashepses which appears completely adult and could be mistaken for a husband of Pepi (indeed, see above) requires the label "her son" to make clear his role in the family. The problem with this interpretation is that the statue is clearly focused on Pepi, rather than her son, and in pseudo-groups the repeated figure is most often the statue owner and most important figure. 3) Pepi, with her TWO sons, both of whom are named Rashepses. This giving more than one child the same name is not that unusual, although it is by no means the norm in the Old Kingdom. In that case, the reasoning used above holds true (the child figure does not require [sA=s] because it is clear that he is a son, while the adult figure needs the label for clarity). SInce it is hard to believe that a wife would be shown in the center of a group statue towering over her husband, or that she would have such an important position in a pseudo-group where her son was the duplicated figure (and hence, probably the commissioner of the piece), it seems most likely that Pepi was the dedicator of the piece, which would explain her depiction with two juvenile sons and why she was the main figure of the group.

-

- Type Attested

- Remarks Appears as one of two male figures named Rashepses in limestone standing group statue (Hildesheim 17) of Pepi and her sons (?); Rashepses identified as [wab nswt] royal wab-priest; found displaced in D 23, shaft 5. There are three possibilities as to who is actually represented in this statue: 1) Rashepses, his wife Pepi, and their son Rashepses. If this is true, then the craftsman who inscribed the piece switched the two Rashepses inscriptions, labeling the man as [sA=s raSpss] "her son Rashepses" and the boy as [wab nswt raSpss] "royal wab-priest Rashepses". This seems unlikely because the focal point of the group (the central, largest figure) is clearly Pepi, which would be quite unusual in a normal family statue. Also, the son is labeled "her son", not "his son" or "their son". 2) A so-called "pseudo-group", representing Pepi with her son Rashepses who appears twice at different ages. If this is the case, then the labels are more understandable; as a small boy, his size, nakedness and side lock all indicate that Rashepses must be the son of a nearby adult (i.e. Pepi) without it needing to be spelled out. However, the larger figure of Rashepses which appears completely adult and could be mistaken for a husband of Pepi (indeed, see above) requires the label "her son" to make clear his role in the family. The problem with this interpretation is that the statue is clearly focused on Pepi, rather than her son, and in pseudo-groups the repeated figure is most often the statue owner and most important figure. 3) Pepi, with her TWO sons, both of whom are named Rashepses. This giving more than one child the same name is not that unusual, although it is by no means the norm in the Old Kingdom. In that case, the reasoning used above holds true (the child figure does not require [sA=s] because it is clear that he is a son, while the adult figure needs the label for clarity). SInce it is hard to believe that a wife would be shown in the center of a group statue towering over her husband, or that she would have such an important position in a pseudo-group where her son was the duplicated figure (and hence, probably the commissioner of the piece), it seems most likely that Pepi was the dedicator of the piece, which would explain her depiction with two juvenile sons and why she was the main figure of the group.

-

- Type Attested

- Remarks Appears as one of two male figures named Rashepses in limestone standing group statue (Hildesheim 17) of Pepi and her sons (?); Rashepses identified as [sA=s] her son; found displaced in D 23, shaft 5. There are three possibilities as to who is actually represented in this statue: 1) Rashepses, his wife Pepi, and their son Rashepses. If this is true, then the craftsman who inscribed the piece switched the two Rashepses inscriptions, labeling the man as [sA=s raSpss] "her son Rashepses" and the boy as [wab nswt raSpss] "royal wab-priest Rashepses". This seems unlikely because the focal point of the group (the central, largest figure) is clearly Pepi, which would be quite unusual in a normal family statue. Also, the son is labeled "her son", not "his son" or "their son". 2) A so-called "pseudo-group", representing Pepi with her son Rashepses who appears twice at different ages. If this is the case, then the labels are more understandable; as a small boy, his size, nakedness and side lock all indicate that Rashepses must be the son of a nearby adult (i.e. Pepi) without it needing to be spelled out. However, the larger figure of Rashepses which appears completely adult and could be mistaken for a husband of Pepi (indeed, see above) requires the label "her son" to make clear his role in the family. The problem with this interpretation is that the statue is clearly focused on Pepi, rather than her son, and in pseudo-groups the repeated figure is most often the statue owner and most important figure. 3) Pepi, with her TWO sons, both of whom are named Rashepses. This giving more than one child the same name is not that unusual, although it is by no means the norm in the Old Kingdom. In that case, the reasoning used above holds true (the child figure does not require [sA=s] because it is clear that he is a son, while the adult figure needs the label for clarity). SInce it is hard to believe that a wife would be shown in the center of a group statue towering over her husband, or that she would have such an important position in a pseudo-group where her son was the duplicated figure (and hence, probably the commissioner of the piece), it seems most likely that Pepi was the dedicator of the piece, which would explain her depiction with two juvenile sons and why she was the main figure of the group.

Modern People

-

- Type Excavator

- Nationality & Dates German, 1861–1951

- Remarks Egyptologist and Copticist. Nationality and life dates from Who was Who in Egyptology. (1861-1951) German Egyptologist and Copticist; he was born in Dessau, 12 Nov. 1861, son of Ludwig S. and Helen S.; he was educated at the Universities of Berlin and Gottingen, and was Erman's (q.v.) first student; Ph.D. Gott., 1884; afterwards appointed assistant in Berlin Museum, 1885-93; Professor of Egyptology at Leipzig, 1893 until 1938, where he founded the Egyptian Institute and filled it with objects from his excavations in Egypt and Nubia; Steindorff made a special study of Coptic and was with Crum (q.v.) the leading authority in the world during his lifetime; he was also interested in art and published books and articles on this subject as well as on Egyptian religion; he explored the Libyan Desert, 1899-1900; excavated at Giza, 1909-1 1, and in Nubia, 1912- 14 and 1930-1; he edited the ZAS for 40 years and contributed many articles to it; his studies in Coptic were of the utmost importance and his Coptic Grammar still remains a standard work of reference and perhaps the most popular ever written in this field; in philology as a whole he was in the first rank and established the rules which are gener- ally accepted for the vocalization of Egyptian; in 1939 he was forced to emigrate to America when the Nazis were in power in Germany, and started another career there at the age of nearly eighty; he continued his studies in the museums of New York, Boston, and Baltimore and the Oriental Institute of Chicago; Hon. Member of American Oriental Soc.; at Baltimore he compiled a 12-vol. MSS Catalogue of Egyptian antiquities in the Walters Art Gallery, which formed the basis for a later pub. work; both his 70th and 80th birthdays were the subject of tributes, see below; his published works are very numerous and his bibl. lists about 250 books, articles, and reviews, the first of which appeared in 1883, the last in the year of his death nearly 70 years later; Sassanidische Siegelsteine, with P. Horn, 1891; Koptische Grammatik mit Chrestomathie, Worterverzeichnis und Literatur, 1894, rev. ed. 1904; Grabfunde des Mittleren Reiches in den Koniglichen Museen zu Berlin. I. Das Grab des Mentuhotep, 1896; Die Apokalypse des Elias, eine unbekannte Apokalypse und Bruchstücke der Sophonias-Apokalypse. Koptische Text, Ubersetzung, Glossar, 1899; Die Blütezeit des Pharaonenreiches, 1900, rev. ed. 1926; Grabfunde des Mitt, Reiches in den Koniglichen Mus, zu Berlin, II. Der Sarg des Sebk-o. Ein Grabfund aus Gebelên, 1901; Durch die Libysche Wüste zur Amonoase, 1904; The Religion of the Ancient Egyptians, 1905; Koptische Rechtsurkunden des Achten Jahrhunderts aus Djëme, Theben, with W. E. Crum, 1912; Das Grab des Ti. Veroffentlichungen der Ernst von Sieglin Expedition in Agypten, vol. 2, 1913; Aegyten in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart, 1915; Kurzer Abriss der Koptischen Grammatik mit Lesestücken und W?rterveyzeichnis, 1921;Die Kunst derAegypter. Bauten,Plaslik, Kunstgewerbe, 1928; Aniba, 1. Band with R. Heidenreich, F. Kretschmar, A. Langsdorff, and W. Wolf, 11. Band with M. Marcks, H. Schleif, and W. Wolf, 1935-7; Die Thebanische Graberwelt, with W. Wolf, 1936; When Egypt Ruled the East, with K. C. Seele, 1942; Egypt, text of Hoyningen-Huene, 1943; Catalogue of the Egyptian Sculpture in the Walters Art Gallery, 1946; Lehrbuch der Koptischen Grammatik, 1951; while in America he also wrote a Coptic-Egyptian Etymological Dictionary; The Origin of the Coptic Language and Literature: Prolegomena to the Coptic Grammar; The Proverbs of Solomon in Akhmimic Coptic according to a Papyrus in the State Library in Berlin, with a Coptic-Greek Glossary compiled by Carl Schmidt, he also edited many editions of Baedeker's Egypt, making it a standard work for all travellers and the best general guide available; he died in Hollywood, California, 28 Aug. 1951. AEB 28, 29; Bulletin Issued by. the Egyptian Educ. Bureau, London, n(. 58, Sept. 1951. 25 (anon);Chron. D'Eg.27 (I952), 391;JA0S 61 (1941), 288-9, Eightieth Anniversary. of Prof.Steindorff,J.H Breasted Jnr.;66.(1946), 76-87, The Writings of Georg Steindroff , J.H.Breasted Jnr.; 67 (1947) , 141-2,326-7; JEA 38 (1952), 2; Kürschner Corr .; The Times , 30 Aug. 1951; ZAS67 (1931), 1, Seventieth Birthday Tribute; ZAS79 (1954) , V-VI (portr.)(S.Morenz); E. Blumenthal,Altes ?gypten in Leipzig, 1918, 15-31 .

Name of this image

Description of the image duis mollis, est non commodo luctus, nisi erat porttitor ligula, eget lacinia odio sem nec elit. Sed posuere consectetur est at lobortis. Donec sed odio dui.

- Heather ONeill heather@pixelsforhumans.com

- Nicholas Picardo npicardo@fas.harvard.edu

- Luke Hollis luke@archimedes.digital

Hi ! (not you? Login to your account.)

- Cole Test Collection - Tomb Chapels and Shafts

- GPH Test Collection 1

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- ZAP

- ZAP

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Ankhmare

- ZAP

- ZAP

- ZAP

- Hello World

- http://www.pypi.org/

- Hello World

- //pypi.org

- Hello World

- Hello World

- 1'2"3

- a'b"c'd"

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- /..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//../etc/passwd

- Hello World

- Hello World

- ../../../../../../../../../../../../../../../etc/passwd

- Hello World

- file:///etc/passwd

- /etc/passwd

- /..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//../boot.ini

- ../../../../../../../../../../../../../../../boot.ini

- Hello World

- C:\boot.ini

- file:///C:/boot.ini

- file:///C:/win.ini

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- &&/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- &&type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- |/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- |type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- ;/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- ;type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World

- `/bin/cat /etc/passwd`

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello Worldtype %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World&&type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World&&/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- run type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World|/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World|type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World;/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello Worldrun type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World`/bin/cat /etc/passwd`

- Hello World type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World;type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Mr.

- Hello World

- Hello World

- a'b"c'd"

- 1'2"3

- Hello World

- http://www.pypi.org/

- Hello World

- //pypi.org

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- ../../../../../../../../../../../../../../../etc/passwd

- /..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//../etc/passwd

- /etc/passwd

- /..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//../boot.ini

- ../../../../../../../../../../../../../../../boot.ini

- file:///etc/passwd

- C:\boot.ini

- file:///C:/win.ini

- %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- file:///C:/boot.ini

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World

- &&/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- &&type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- |type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- |/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- ;type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- ;/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- `/bin/cat /etc/passwd`

- run type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello Worldtype %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World&&/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World&&type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World|/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World|type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World;/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World;type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World`/bin/cat /etc/passwd`

- Hello Worldrun type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World`/bin/cat /etc/passwd`

- Hello Worldrun type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World

- 1'2"3

- Hello World

- a'b"c'd"

- Hello World

- Hello World

- //pypi.org

- http://www.pypi.org/

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- /..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//../etc/passwd

- ../../../../../../../../../../../../../../../etc/passwd

- /etc/passwd

- ../../../../../../../../../../../../../../../boot.ini

- /..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//../boot.ini

- file:///etc/passwd

- C:\boot.ini

- %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- file:///C:/boot.ini

- file:///C:/win.ini

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- &&/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- ;/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- &&type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- |type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- ;type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- |/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World

- `/bin/cat /etc/passwd`

- Hello World

- Hello World

- run type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World|/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World

- Hello World&&type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World|type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello Worldtype %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World&&/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World;/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World;type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World`/bin/cat /etc/passwd`

- Hello Worldrun type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World

- 1'2"3

- Hello World

- a'b"c'd"

- http://www.pypi.org/

- Hello World

- //pypi.org

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- /..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//../etc/passwd

- ../../../../../../../../../../../../../../../etc/passwd

- /etc/passwd

- file:///etc/passwd

- /..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//..//../boot.ini

- ../../../../../../../../../../../../../../../boot.ini

- %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- C:\boot.ini

- file:///C:/boot.ini

- Hello World

- file:///C:/win.ini

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- &&/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World

- Hello World

- /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World

- &&type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- |/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- |type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- ;/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- ;type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World

- type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World

- /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- `/bin/cat /etc/passwd`

- type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- run type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World

- Hello World/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World

- Hello Worldtype %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World;type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World;/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World&&type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World|/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World&&/bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World

- Hello World type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World|type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello World`/bin/cat /etc/passwd`

- Hello World /bin/cat /etc/passwd

- Hello World type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello Worldrun type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Hello Worldrun type %SYSTEMROOT%\win.ini

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- )

- HttP://bxss.me/t/xss.html?%00

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- !(()&&!|*|*|

- bxss.me/t/xss.html?%00

- Mr.

- Mr.

- ^(#$!@#$)(()))******

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- ;assert(base64_decode('cHJpbnQobWQ1KDMxMzM3KSk7'));

- )))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- ';print(md5(31337));$a='

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.<esi:include src="http://bxss.me/rpb.png"/>

- ";print(md5(31337));$a="

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- ${@print(md5(31337))}

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- ${@print(md5(31337))}\

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- '.print(md5(31337)).'

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- 1yrphmgdpgulaszriylqiipemefmacafkxycjaxjs%00.

- Mr.

- response.write(9359478*9159837)

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Http://bxss.me/t/fit.txt

- Mr.

- Mr.

- '+response.write(9359478*9159837)+'

- Mr.

- http://bxss.me/t/fit.txt%3F.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- "+response.write(9359478*9159837)+"

- Mr.

- /etc/shells

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- ../../../../../../../../../../../../../../etc/shells

- Mr.

- Mr.

- c:/windows/win.ini

- Mr.

- Mr.

- bxss.me

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- '"()

- Mr.'&&sleep(27*1000)*slthro&&'

- Mr."&&sleep(27*1000)*dkdlrh&&"

- Mr.'||sleep(27*1000)*pfyeyf||'

- Mr."||sleep(27*1000)*vrrigp||"

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.HpwZ3hXw

- Mr.

- Mr.

- Mr.

- -1 OR 2+803-803-1=0+0+0+1 --

- Mr.

- -1 OR 2+253-253-1=0+0+0+1

- Mr.

- -1' OR 2+807-807-1=0+0+0+1 --

- Mr.

- -1' OR 2+110-110-1=0+0+0+1 or 'mIlFOcgT'='

- Mr.

- -1" OR 2+293-293-1=0+0+0+1 --

- Mr.

- if(now()=sysdate(),sleep(15),0)

- Mr.

- Mr.0'XOR(if(now()=sysdate(),sleep(15),0))XOR'Z

- Mr.

- Mr.0"XOR(if(now()=sysdate(),sleep(15),0))XOR"Z

- Mr.

- Mr.-1 waitfor delay '0:0:15' --

- Mr.2H1Mv5Ef'; waitfor delay '0:0:15' --

- Mr.TYNbmTdK' OR 776=(SELECT 776 FROM PG_SLEEP(15))--

- Mr.

- Mr.80a8vca7') OR 501=(SELECT 501 FROM PG_SLEEP(15))--

- Mr.2DjcVzD1')) OR 104=(SELECT 104 FROM PG_SLEEP(15))--

- ../../../../../../../../../../../../../../etc/passwd

- Mr.'||DBMS_PIPE.RECEIVE_MESSAGE(CHR(98)||CHR(98)||CHR(98),15)||'

- ../../../../../../../../../../../../../../windows/win.ini

- Mr.

- file:///etc/passwd

- Mr.'"

- Mr.

- Mr.����%2527%2522\'\"

- ../Mr.

- @@kojE8

- Mr.